My family moved from the great state of Missouri to a rural ranching county in Montana when I was sixteen.

The roofing paid better in Montana, my dad said. I would be permitted to wear skirts and shirts again, and unpack my necklaces -- I'd only worn dresses I'd made. And so I was towed out west with my three hundred thrifted novels and nine younger siblings.

I missed the Amish and their work holidays. I despised the hostile landscape where instead of rolling, green hills or abundant roadside wildflowers there were only snow-capped, dry rocky mountains. We moved into the middle of a small town, population fifty-five, and walked down a long, barren gravel road. Neighbors passed on their ATVs, but nobody returned our friendly waves.

They glared.

Eventually we made friends, because we weren't shy. My brothers stopped wearing suspenders and straw hats to fit in with the other boys. We girls kept wearing our skirts -- we were too tough for the mockery of our peers, and would return it with, "Don't you know it looks weird to paint your eyelids green?"

However mockery grates at even the most calloused of souls. And I found a greater wedge being driven between me, the almost Amish girl, and those who were fourth and fifth generational ranchers1. I didn't find their deprecating jokes funny.

Sometimes I would be reminiscent. "I miss the trees we had in Missouri!"

And my friends would be offended. "What do you mean? We have trees!"

I knew then they didn't know what trees meant — they'd never been to Missouri. To them trees were always green, sparsely grown, and easily burnt to ash in regular forest fires. Instead of ponds and creeks and hardwood trees with leaves that turned color they had sage brush, and sometimes lupine. Instead of lizards and turtles and frogs and possums they had rattle snakes and mosquitoes. I forgot the unknown dangers of the woods — the wild boars, the rabid raccoons, the quiet, camouflaged copperheads, the cotton mouth snakes carried by the river currents, cougars, and other wild cats. Montana had bears, supposedly. In my eight years there I only ever saw a cub.

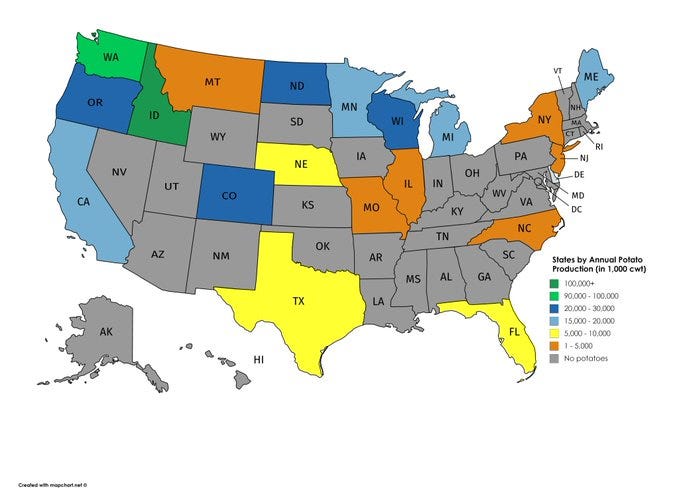

The ranchers weren't even real ranchers anymore — nobody had a horse. They had cows — that they injected a lot of hormones into — and potatoes. They had Murdoch's.

For a time, I didn't like cows and potatoes. I preferred venison. Raw milk was illegal, until I got on a podcast with a friend (who also wasn't from Montana) and the policy was changed. And then it was $10 a gallon. You can still get it for about a dollar or two in Missouri, sometimes four.

As I left my teen years behind me I forced an emotional truce with Montana and desisted comparing it to Missouri. I recognized the imperfections of my home state, and realized I wouldn't ever go back for a myriad of reasons. I thought perhaps I could reconcile myself to the West, maybe even marry and have a family there. I made real friends.

However it was always a farce.

It wasn't ranchers who I made friends with, but out-of-staters. My friends were all the quirks from open-mics, college campuses, and the Christians at various churches who had the courage to voice their own doubts. I forgot my love for trees and wild flowers and babbling brooks. The visceral illness I felt was shoved deep inside, and I learned to enjoy hiking over the scorched, prickly plains up into high altitudes where everything seemed wild -- but it was too calm, too safe, too quiet. There were no beasts.

I laid my dissatisfied complaints out of mind for years because I was led to believe that everyone loves Montana and nobody cares for the Midwest. I was told I had healing to do, there must be something wrong with me if I couldn't accept and recognize just how great Montana was compared to all of the other states. Make Montana Great Again, locals said, while smugly believing it had and always would be the greatest state.

"Why aren't you happy to be in Montana? It's free here. And we're feeding the world with our cows and potatoes."

I knew I didn't want to raise children in a place where there was no forest in which to play hide and seek, or where girls were too afraid to wear dresses because beauty is ridiculed. I didn't want to raise sons in a place where the men scorn women unless they're mannish. I didn't want to have a family in a place where it's normal to be hostile to strangers, where the mainstream non-denominational churches preach grace but are unable to accept anyone who's not like them, and where the property taxes are comparable to California and more than Massachusetts.

For years I was gas-lit to believe one couldn't question the superiority of Montana - or of the West.

I was reminded to have grace... to pity these people who have willingly suffered in a difficult climate for centuries so that they might continue to feed the rest of the states. What would we do without Montanan ranchers? I was reminded that it's cold in Montana, and yet the ranchers pull on their $130 insulated Muck boots to visit their cows. Sure, everyone is inhospitable. That's how it is in a climate where the freezing wind mixes with the marrow of the bone. Everyone is forced to be tough and calloused. They've learned the hard way that you trust who you trust, and you don't give anyone else the time of the day. If you're a rancher you're a part of a specific culture where the men where jeans and boots, and where the women also wear jeans and boots with plastic-gem studs sewn onto the back pockets. The men wear silk scarves and custom-shaped hats. The women have fringe on their rattle-snake skin purses. Everything is Western cut: the snapped shirts, the water bottles, the frowns, the Chevy trucks. You do it their way - you're born and raised in progressive cowboy land -- or you're probably from California (Missouri might've well as been California).

The only real instance of racism I ever saw was in Montana when a local cop harassed a black man that was living with us because some old lady in our town complained about him. However, ranchers aren't open to diversity. Only efficiency. They don't want culture. They want high ceilings and Fox News and painted cattle skulls.

Wolves are bad because they tear up baby calves - the only sight that might make the most hard-hearted rancher weep. Their custom shaped cowboy hats say they don't trust the government, but in reality they love their Purple Politicians. Private Property means they feel they ought to have the right to shoot anyone sleeping in the bush a mile from their house. They have guns and trucks and hats. And they are feeding the world by the sacrifice of their labor - this is why you have potatoes and beef on your plate. So you better submit to their sterile, profit-for-wealth mentality or go to some other state where there's more room.

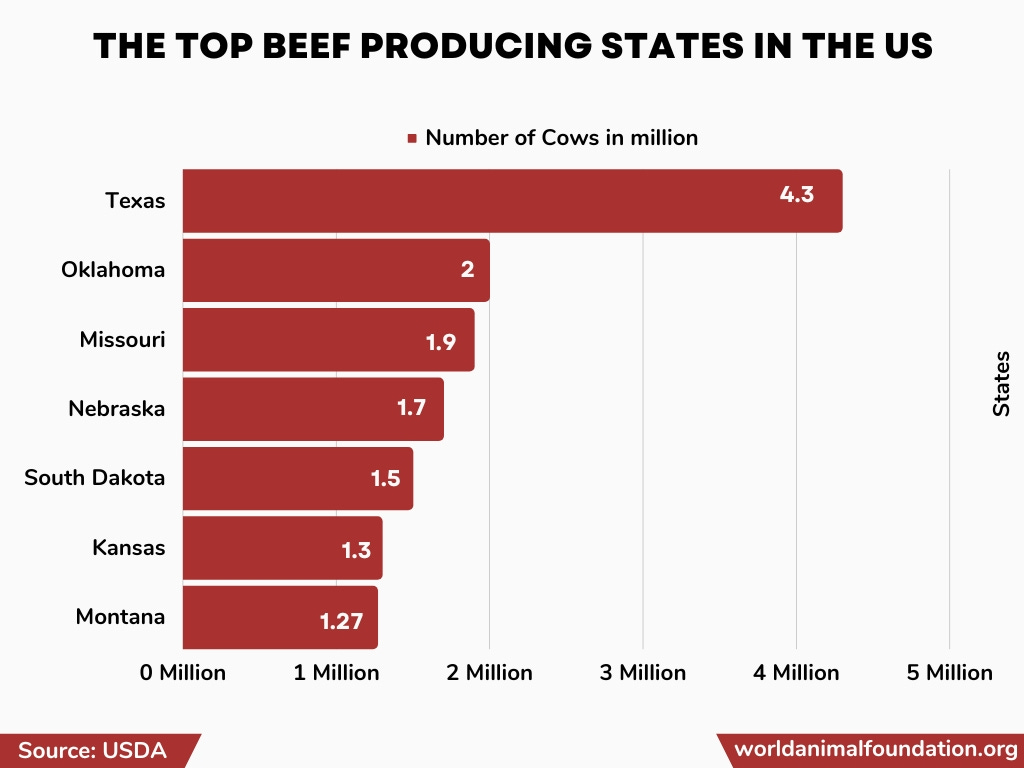

Imagine my shock recently when I discovered that Missouri produces more beef than Montana and with only about ten percent of the land needed in Montana to graze cows.

Who is it that actually keeps burgers and steaks on our plates? Potatoes?

Missouri doesn't have a Murdoch's, but the ranchers are friendlier. Some of them even wear dresses while branding. Ranching is not their entire personality. Unlike Montana, Missouri has more than cows and sagebrush. In fact, it’s easy to know someone who raises beef cows well without ever talking about cows with you. You might even forget that they have cows. I didn’t know this until recently, however the man who is a long family friend of both sides of our family and who introduced my parents . . . has cows. A lot of cows. He’s not just a rancher, he’s also owns a junk yard of obscure cars, is a regular driver for the Amish, a Vietnam vet, and an eccentric Christian. Needless to say his identity is not wrapped around his cows, and he’s never said things like “if it weren’t for my hard-work and endless sacrifice, the world would starve” although it would be fair for him to say it as much as anyone.

Western ranchers do go through a lot, and yes many of them have been here for several generations — their great-great grandfathers were all disappointed gold miners. They’ve grown to love how rough the winter is. Their ideology has formed around their psychology: they are doing the world a service by taking up the path of the hermit cow-herder. They may never have many friends, their children might be forced to choose between staying on the ranch or finding a spouse. If a suitor comes around he better have proof that he can afford to purchase his own thousand acres and fifty cows. The churches are small; the music is heartfelt, but communion is stiff. There’s no time to talk about feelings and dreams until the cows are branded and shipped. There’s a lot of land to cover.

I digress.

I do not wish to do to fully belittle the Montanan spirit. Not everyone there is a rancher. They have oil, too, along with their fair share of sportswear outlets, ski resorts, and remote jobs. They have rodeos and cowboy churches.

As Edward Abbey writes:

The rancher (with a few honorable exceptions) is a man who strings barbed wire all over the range; drills wells and bulldozes stock ponds; drives off elk and antelope and bighorn sheep; poisons coyotes and prairie dogs; shoots eagles, bears, and cougars on sight; supplants the native grasses with tumbleweed, snakeweed, povertyweed, cowshit, anthills, mud, dust, and flies. And then leans back and grins at the TV cameras and talks about how much he loves the American West. Cowboys are also greatly overrated. Consider the nature of their work. Suppose you had to spend most of your working hours sitting on a horse, contemplating the hind end of a cow. How would that affect your imagination? Think what it does to the relatively simple mind of the average peasant boy, raised amid the bawling of calves and cows in the splatter of mud and the stink of shit.

Do cowboys work hard? Sometimes. But most ranchers don’t work very hard. They have a lot of leisure time for politics and bellyaching.

When I was deciding where to have my wedding, one of my aunts told me that unless I had in Montana she wouldn’t attend. “Oh, I can afford to travel,” she said. “I just won’t attend a wedding if you aren’t doing the proper thing by having it where you’re from.”

“But I’m not from Montana,” I said. “I don’t even like Montana all that much.”

“It sounds like you have some healing to do,” she said.

I had my wedding where I wanted it — Upstate New York — and my aunt didn’t come, nor did she allow my cousins to attend. I was miffed. I thought over words, and how she said I had some healing to do, and I wondered if there was any truth to that.

Do I need to reconcile myself to idolizing Montana over any other place I choose to love? Was it important for me to learn to love Montana? What of California, then? A place all Montanans equally hate? Or Florida? Or Delaware? What was wrong with me loving Missouri — or Upstate New York most?

I thought back to the times where I used to leave on long road trips, of how I always felt so free with Big Sky country at my back and forests before my vision, and of happy I would become. And yet, whenever I returned to Montana, and inhaled the Big Bare Skies of the West again, I would feel hope . . . that maybe I was returning home finally. I sincerely stopped hating Montana in my early twenties, but always, after only a couple weeks home, I felt myself stagnating again, longing for the trees and wildflowers and babbling brooks, where everyone was weird and friendly, and the culture was too convoluted to be sterile or homogeneous.

Even if I were odd-looking, I didn’t feel out of place in the Midwest or East. I felt whole and happy — and my thoughts of Montana and its ranchers turned kinder, too.

My husband sometimes speaks of one’s metaphysical connections to their geography, and I think the “us vs others” mentality is an uninformed symptom of this truth. We’re simply an extension of our own roots. We are largely formed by where we’re from — and our loyalty and love will be to that place. When we accept this we’re better able to appreciate others and we’re they’re at. Especially if we’re not forced to change. Perhaps I would never have come to despise the Montana ranchers and the Western Ethos if I hadn’t felt like I had to choose between them or my childhood paradise.

My husband and I went West this summer after our wedding.

He, a man who knows his Geography intimately, and is spiritually aware of where his soul belongs, was able to say, “Look at how beautiful the sky is!”

I, on the other hand, had all the weight of the past stirring in my heart and said, “Why do you think so? I hate the West.”

He said, “Oh, c’mon. Give it a chance.”

“The don’t even know how to have fun unless it’s a rodeo,” I complained.

“What’s wrong with rodeos?”

For we had agreed that if we could fall in love with a place, and if the place could fall in love with us we would stay there and raise a family. My heart was hardened — it could not see the beauty of naked skies and earth-ready-to-be-scorched. Mostly, I knew how mean ranchers could be, and how conceited they were, and how they all dressed the same and hated those who didn’t dress as they dressed.

I already knew why I hated the West. Why should I be open to it?

Our bus driver seemed to have a death wish — or to not fear death. He was detached and uncommunicative, and driving too fast in a wind storm, passing swaying semis and overloaded trailers. My husband and I decided we’d get off at the very next stop, and found ourselves . . . in the midst of Wyoming’s State Fair and Rodeo.

The air was clean. And I had to admit the men here dressed better than most men do. One could argue that they dressed better than the woman — or that the women dressed basically like the men. Either way, I laid aside my defensive prejudices, and enjoyed the weekend with my husband.

We found an immaculate free campground and set up camp.

I washed the laundry in the nearby creek, and then we went to a bar — where the woman wore crude shirts and booty shorts and glared at me — I was barefoot, in an ankle length skirts, my hairy armpits revealed, and wearing a lace head covering. We were paying customers, so they served us, but the women were patronizing to me while speaking respectfully to my husband — I knew it must be because of how I was dressed. I felt a little more unkindly toward the west.

We found a darling, overpriced thrift store. We wandered around the fairgrounds and stumbled into a tent where a bunch of old ladies were reading through the Bible out loud — they’d made it to the minor prophets. A Mexican trucker was selling beef jerky he’d made — we bought some, and wished later we’d purchased more. And then we went to the parade where they threw so much candy the children couldn’t collect it all. It melted into the streets and was flattened into the pavement by pedestrians and automobiles.

There’s excess, even here in the land of oil and cows and potatoes2, I thought.

A woman with a beautiful smile saw Andy and I sitting on the curbside, and she came over to us to ask us about our bikes. She was the first person to approach us even though we’d been in this town for nearly four days. She was friendly — she saw that we were different, but she was interested and had no judgement in her eyes. She told us that she home schooled, and about her children, and invited us to church.

The next day after church, she and her husband invited us home for lunch. Her children were there, conversational and curious. Their home was typical for the west — spacious ceilings, woven, red rugs, and skulls. But they were welcoming us into it, and the things that I might have hated about it had it been someone else’s home, I now found quaint, charming, and inviting.

I laid aside my own projections, and felt welcomed.

I wondered, “How could these nice people remain in such hostile, hypocritical territory"?”

It was their landscape. They knew it and loved it despite good or bad neighbors. This was their home — just as it would (and could) never be mine. I, too, will someday overlook the inconsistencies of my own home wherever that might be out of love. And I will welcome strangers and feed them and talk to them, and invite them to stay if the land appeals to them . . . or bless them if they must wander elsewhere.

Just as those Wyoming strangers did for us.

I might never love Montana as much as I did Missouri. I will never think the sky is more gorgeous there simply because the land is scorched bare. I won’t ever have much respect for western ranchers as a group of people (I love my friends who are ranchers, though). I don’t like their fashion or how they party. I don’t think I can completely understand the stiff, cold inhospitable nature of the west, or its gold-fever lust for cows and oil.

However, I have come to appreciate the many ways to use sage — from incense to spice — and I think that’s something of what it looks like to heal.

Montana was a fine place to visit, and I’m glad I have friends there, as much as anywhere — but it’s not a place to be if the world’s ending.

Missouri is better, from my perspective.

My Substack is free to readers, but if you want to send me a donation you can do so here:

A rancher is someone who has lot of leisure time for politics and bellyaching., according to Edward Abbey in “Cowburnt”

One my of staple dishes to make when company comes over is potatoes and meat (venison or beef) and oil (olive) rubbed in sage. This is my tribute to the West.

I have used some of the same tropes about cowboy culture myself. Having grown up in it(somewhat), moved away and now returned home. What I’ve noticed with fresh eyes and a little bit less youthful reactionary tendencies is that despite its faults it at least is a culture.

I know a family who has been in my town since before there was a town. They’ve ran cattle, owned the auction market, very involved with our local rodeo etc. There is certainly some superficialities that come along with some of this stuff and it’s not all to my taste but they have a real coherent sense of themselves and their family story. They have walls of pictures of ancestors and know the stories if their patriarchs and matriarchs When there is a family celebration or mourning, they come together and renew the bond. Maybe it’s just the beginning, and a very incomplete one, but it’s the only way we can cultivate love for place and the virtue of fidelity. It’s a gift for future generations here.

I lived in WA state a long time. And I still love the dry parts but have had my fill of forests. And I had to leave because there were too many memories of husband 1 & 2 in those places and I was sad all the time. I wound up in rural KS. I don't expect to ever fit in like those born and raised here. I love that top of the world feeling when you can see for miles. I like that we waive at each other. I wear my long skirts and Birkies and take my dog to the lake every day. I don't have any close friends but am finally able to take part in some activities. And I'm happy most of the time. It's enough.